Ska in the 90s: An Interview with Aaron Carnes

After writing a book about punk in the 1990s, I was excited to stumble upon Aaron Carnes’ book In Defense of Ska, which comes out in May 2021 and is available for pre-order from Clash Books. Punk has long had a love/hate relationship with ska, with the two genres cross-fertilizing one another, especially in the 1990s. Ska’s history stretches back to the 1950s and the genre remains vibrant today. In Defense of Ska is a passionate defense of the music against its detractors with lots of history, first-hand accounts, and no shortage of humor. I interviewed author Aaron Carnes to learn more about the relationship between punk and ska and about ska in the 1990s. I especially like that Aaron corrects some of my own faulty assumptions in this interview, including the problem with the term “Third Wave Ska.” Hands down my favorite part of this interview is when Aaron sardonically notes that “punks acted like they never skanked at a Let’s Go Bowling show” when ska stopped being “cool”…so true!

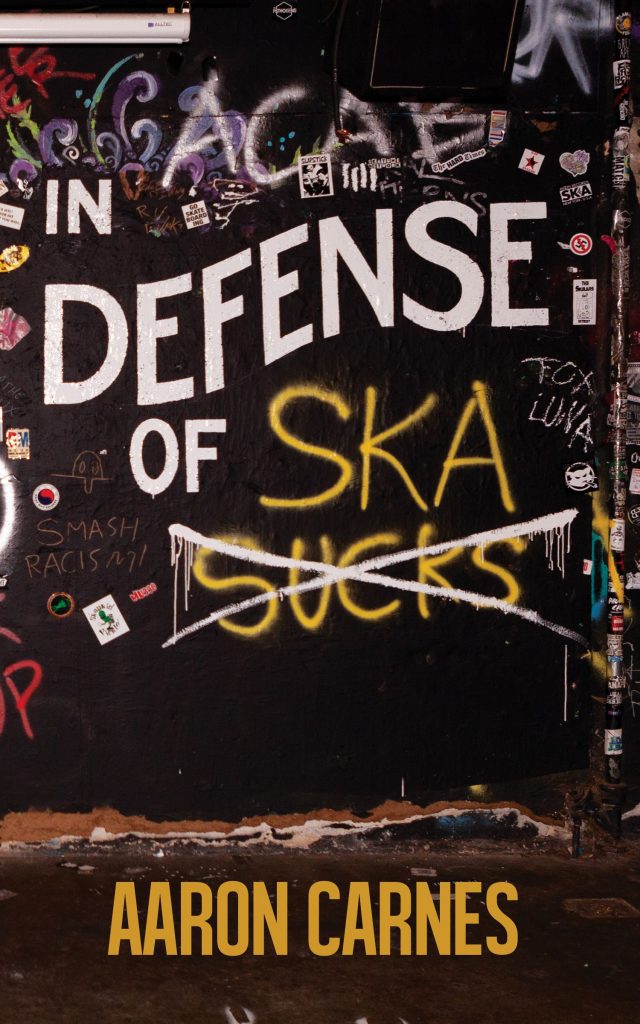

In Defense of Ska book cover by Cam Evans (IG: @photofromcam).

Why did Third Wave ska get so big in the 1990s? Who was the audience for it, how did the scene get built, and what was the appeal?

The reason ska in the ’90s is referred to as Third Wave was because the music started in Jamaica in the ’50s and ’60s, was then revived and melded with UK punk in the late-70s, and then for a brief period of time gained a mainstream audience in the US in the mid-to-late 90s. I don’t care for this narrative because it fails to take into account just what was happening in the US between the Second and Third waves. 2 Tone ska in the late ’70s was top-40 pop music in the UK. In the US, the music only gained a cult audience. However, it was a passionate fanbase. Local groups popped up in every major city in the early ’80s and built huge underground scenes. By the mid-to-late 80s, these bands were constructing a touring network, ska record labels were forming, and zines and compilation albums flourished. Ska in the early ’90s was one of the most exciting, successful DIY scenes that had been built slowly and methodically. Bands that were getting zero interest from record labels were able to make a living from indie record sales and concert tickets. Record labels should have taken an interest in ska in the ’80s, but since the 2 Tone bands didn’t chart here, they figured that the local bands probably wouldn’t do better.

But eventually, the success of ska was too big to ignore. In February 1993, Robert Hingley from the Toasters threw a sold out 2,500 person concert in New York called Skalapalooza. Off of the success of that show, he then booked a four-week tour called Skavoovee. The package included Skatalites, Special Beat, The Toasters and local openers. They played packed houses (1,000-2,500 crowds) every night. Industry folks took notice. But the question is why was it that punk-ska bands that got all the radio play? At the same time, punk rock went mainstream via Green Day and Offspring, so it was much more marketable. And the first few ska singles in 1995 were flukes. Sublime’s “Date Rape,” a song 3 years old by then, got random airplay on KROQ in L.A. and a sudden bursts of listener requests threw it into regular rotation. And then Rancid, a punk band who were avid ska lovers, decided to release the 2 Tone inspired “Time Bomb.” Their label, Epitaph, supported them. At this time, the ska audience was very diverse. Kids from all walks of life went to ska shows. It wasn’t until a year or two later that the labels started defining ska as goofy music and that the audience got pigeonholed to being nerdy kids that wore checkered pants and fedora hats. That’s not what it was before MTV deemed it the latest trend.

What were the defining musical stylistic features of Third Wave ska, and how does it differ from other waves of ska?

Third Wave isn’t a term I care for because there wasn’t really a mid-90s wave of ska. It was a continuous underground scene that connected back to the Second Wave, known as 2 Tone. And even if you take a snapshot of ska bands that were active in 1996, there isn’t anything that defines them all. Some bands, like Reel Big Fish, were goofy and mixed pop-punk and ska, but at the same time, you had a band like Hepcat who drew mostly from traditional Jamaican ska, modern soul, and some Latin elements. These two bands are both considered Third Wave, and they’re both even from Southern California, but they have almost nothing in common. But if you wanted to make a generalization about how ska changed in the ’90s, I would say that the groups mixed it with a lot more elements than previous generations had. This was largely because of Fishbone, who, in the ’80s, played every style really well, but leaned heavily into ska. They brought a frenetic energy to the music that didn’t really exist before. And they wrote satirical lyrics that criticized our government, drew attention to racism and showed the way modern society dehumanized average people. Most ska bands in the ’90s either wanted to be Fishbone, or they were influenced by a band that idolized Fishbone. But how that manifested was different with each band since Fishbone were so diverse, probably to the detriment of their own success. They were a tough band to market.

Were the Blue Meanies the most intense and weirdest sounding ska band of the 1990s?

It would be hard to find another ska band as weird and intense as the Blue Meanies, though I’d say that some of the Mephiskapheles deep cuts are like a jazzier version of the Blue Meanies. The funny thing about The Blue Meanies was they didn’t consider themselves a ska band. They were just making weird music and drawing from multiple influences. When they were just a local Chicago band, they were primarily part of the punk scene. When they started touring in the greater Midwest, it was the ska bands in other nearby cities that took a liking to them. So, they just became known as a ska band. In the’90s, the Midwest was an odd place for ska. Mostly you only had 1-2 bands per city. And those bands developed their sound and image almost in a vacuum, since they were so far removed from everywhere else. And the industry people rarely took an interest in the Midwest. Bands like Gangster Fun (Detroit), MU330 (St. Louis), Mustard Plug (Grand Rapids), Suicide Machines (Detroit), Pacers (Milwaukee) were all so different from each other. It wasn’t like some of the coastal cities, where you had scenes form with bands that fed off of each other’s style. In New York, a lot of jazz and traditional ska elements seeped into the music. In Northern California, the Gilman punk scene was an influential factor. In Orange County, the bands loved pop-punk. In the context of the Midwest’s unpretentiousness, and spirit of everyone doing their own thing, The Blue Meanies fit right in with the bands, precisely by not fitting in.

How much and in what ways do American ska audiences engage Jamaican culture?

Most American ska fans get into the music from whatever bands are current. That’s just how it works for most genres. If they are casual ska fans, they probably don’t take the time to learn about the roots of the genre. But a majority of people that get really into ska go backwards. That includes 2 Tone and Jamaican ska. I would say that generally, as far are fans of any genre go, ska fans tend to be pretty well educated on the roots of their music. I attribute this to the bands making an effort to talk about the genre, and to even cover songs from earlier eras. 2 Tone bands, 90s bands, even bands today, most of them feel amazed at how this music traveled over time and across different countries. They want to share that with anyone that hears them and is dazzled by this music. How crazy is it that the roots of this music started in the ’50s in Jamaica, and that it even pre-dates reggae?

Were the Mighty Mighty Bosstones responsible for the most recruitment into antifascist organizing in the 1990s? It seems like their concerts were the main way people learned about Anti-Racist Action (ARA).

Most ska bands in the ’90s felt inspired to be anti-racist because the 2 Tone ska bands so overtly linked ska music to anti-racism. Most bands either condemned racism in interviews, wrote anti-racist songs and/or encouraged their fans to get involved, like you’re saying. The Mighty Mighty Bosstones are great guys who hate racism. They had one of the biggest megaphones in ska, and they used it to fight racism, in the same way they saw the 2 Tone bands they loved do so.

I would also like to bring attention to Mike Park, the sax player/singer of Skankin’ Pickle, who later started Asian Man Records and fronted the Bruce Lee Band and The Chinkees. Not only did a lot of his songs condemn racism, but he’s worked really hard throughout his entire career to raise awareness of the problem of racism, and to raise money for anti-racist organizations. In 1998, he put together the Ska Against Racism tour. Disappointed at how he saw ska represented in the mainstream, he wanted to educate all the kids that were getting into ska via MTV where this music came from, and to almost demand they connect it to fighting racism, rather than simply view it as fun music. He ended up feeling disappointed in that tour. He wished there could have been more advocacy at the event and figured that maybe it was too big to control. Subsequently, he organized the Plea For Peace tours, which had the same purpose, but were smaller. Both he, and some bands I spoke with, felt like these tours were more successful at not only bringing an anti-racist message, but also for raising money for food shelters, registering people to vote and helping to fund suicide prevention hotlines. Mike continues to fight the good fight. Last year, he revived Ska Against Racism with a brand new compilation album, and raised a whole lot of money for some awesome anti-racist organizations.

Is there a reason Florida produced lots of ska and grindcore bands?

It is interesting how you had Less Than Jake (one of the biggest 90s ska bands) hail from Gainsville. And then today, Jeremey Andrew Hunter from the SkaTune Network Youtube channel, probably the biggest voice in ska right now, also hails from Gainsville. Ska seems to do well in isolated and off-the-radar places where the kids are craving entertainment, and the people are not concerned with image and looking cool. That is a majority of the state of Florida. But who knows if it’s just a coincidence or not.

Is it accurate to say that punk and ska have a love/hate relationship? And what role do ska-punk bands like Against All Authority play in bridging the two genres?

Back in the ’90s, I felt like the punk and ska scenes overlapped quite a bit. My old ska band usually played with punk bands, and we weren’t even a super punk sounding band. Most punk kids either liked ska, or at least had fun at a punk show. Oddly, the big divide back then was between traditional ska and then every other type of ska. The traditional ska bands drew an audience of rude boys, mods and skinheads. They cared deeply about the fashion and history of ska. They did not care for bands messing up ska with other genres. And they particularly hated bands that called themselves ska that didn’t know how to dress right. You would see angry skinheads giving the stink eye to ska-punk bands. The punk-ska or just general Fishbone-inspired ska bands were a lot less elitist and drew a really diverse audience. Those bands played with punk bands, and just other kinds of alternative rock bands.

When ska got popular, and then particularly when ska fell out of fashion in the mainstream in 1999/2000, you saw a lot of people make fun of the music and run from it. So of course, punks acted like they never skanked at a Let’s Go Bowling show. But they did. And now that culture has continued to push this false narrative that ska was a goofball trend in 1996, more people continue to laugh at the music and the scene, and act like they weren’t part of it in some way. But back in the day, it was really vibrant and diverse and pretty much everyone that went to underground shows could at least appreciate it. I’m glad to see that a lot of the younger bands, and just younger people in general, no longer view ska as a ’90s trend, but see it as a really cool, DIY, politically potent scene that speaks to them.

Where can people buy your book?

My book releases on May 4, 2021. It’s available to pre-order anywhere that books are sold. Amazon, Barnes & Noble, etc. The best way people can pre-order my book is directly from my publisher at clashbooks.com. It’s a little bit cheaper, and you will get it shipped in April.

—

Aaron Carnes. Photo by Amy Bee (IG: @_amy_bee)

Aaron Carnes is a music journalist based out of Sacramento, California. His work has appeared in Playboy, Salon, Bandcamp Daily, Sierra Club, Noisey, Sun Magazine, and he’s the music editor at Good Times Santa Cruz weekly newspaper, where he tries to sneak in ska content whenever his boss isn’t looking.

Aaron has been listening to ska since the early ’90s. He used to play drums in a ska band. Now he just plays ska on his car stereo. When he’s not defending ska, he enjoys backpacking with his wife Amy Bee, and talking about music from every existing genre. Ska will always be his favorite.

Sign up for my newsletter & podcast at https://aaroncarnes.substack.com/

Listen to the In Defense of Ska soundtrack at https://open.spotify.com/playlist/7yBi7Ck8QLisz4qenp62l8?si=LpaOflYUSD2idPH2hlEN8w

Pre-order In Defense of Ska at https://www.clashbooks.com/new-products-2/aaron-carnes-in-defense-of-ska-preorder?fbclid=IwAR32L7KKtozTBL_N2xoAeNtrjBySDPHUgpAYyibW0bSVj9tC_v8vhGR2dFQ